It’s amazing how one interesting tidbit of information can lead to another...and another, and another. Whether hopping through Wikipedia article links or hunting down hard copies of bibliographic citations, the thrill of discovery, of “connecting the dots,” is the fuel to the fire of any research, academic or otherwise.

I found myself fueling one such fire recently. While reading about the controversial removal of multiple statues of Confederate war heroes in New Orleans, I realized that I had no idea who one of these soon-to-be dememorialized men was: Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard. But hey, I then thought, isn’t that surname also the middle name of one Jefferson “Jeff” Beauregard Sessions, current (and perhaps soon-to-be former) Attorney General of the United States?

I pulled up P.G.T. Beauregard’s Wikipedia page to learn that he was a native French-speaking Louisianan who had led Rebel troops to capture Fort Sumter (South Carolina) from Union control, effectively setting off the Civil War in 1861. (At this point I was a little ashamed of my ignorance of my own country’s history.) Beauregard went on to play a pivotal role throughout the conflict and afterwards returned to Louisiana to work as a railroad and state lottery executive.

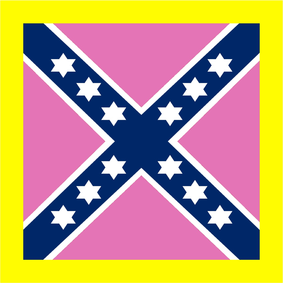

When scrolling through this extensively sourced page, an extremely odd image caught my eye about halfway down: a version of the Confederate battle flag...with a hot pink field instead of its usual blood red. This had to be a joke by some clever internet troll, right? Maybe a strategic “up yours” to the right-wing by rabble rousers from the LGBTQ community in advance of Pride Month?

Nope!

As it turns out, early in the Civil War General Beauregard sought to solve the problem of the CSA’s national “Stars and Bars” flag being constantly confused with the stars and stripes of the Union flag amidst the chaos of the battlefield. He proposed a distinct banner for warfare, the design of which we are familiar with to this day as the favorite symbol of back-country yokels, racist assholes, and revisionist historians. However, since materials were scarce at the time of design, the very first CSA battle flags were made with fabrics donated by several female associates of the General, resulting in a color scheme that was not exactly what we think of when we think of Johnny Reb.

I found myself fueling one such fire recently. While reading about the controversial removal of multiple statues of Confederate war heroes in New Orleans, I realized that I had no idea who one of these soon-to-be dememorialized men was: Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard. But hey, I then thought, isn’t that surname also the middle name of one Jefferson “Jeff” Beauregard Sessions, current (and perhaps soon-to-be former) Attorney General of the United States?

I pulled up P.G.T. Beauregard’s Wikipedia page to learn that he was a native French-speaking Louisianan who had led Rebel troops to capture Fort Sumter (South Carolina) from Union control, effectively setting off the Civil War in 1861. (At this point I was a little ashamed of my ignorance of my own country’s history.) Beauregard went on to play a pivotal role throughout the conflict and afterwards returned to Louisiana to work as a railroad and state lottery executive.

When scrolling through this extensively sourced page, an extremely odd image caught my eye about halfway down: a version of the Confederate battle flag...with a hot pink field instead of its usual blood red. This had to be a joke by some clever internet troll, right? Maybe a strategic “up yours” to the right-wing by rabble rousers from the LGBTQ community in advance of Pride Month?

Nope!

As it turns out, early in the Civil War General Beauregard sought to solve the problem of the CSA’s national “Stars and Bars” flag being constantly confused with the stars and stripes of the Union flag amidst the chaos of the battlefield. He proposed a distinct banner for warfare, the design of which we are familiar with to this day as the favorite symbol of back-country yokels, racist assholes, and revisionist historians. However, since materials were scarce at the time of design, the very first CSA battle flags were made with fabrics donated by several female associates of the General, resulting in a color scheme that was not exactly what we think of when we think of Johnny Reb.

This all still seemed too weird to be true, so I checked one of the sources of this section of the article in the notes. I then checked the online catalog of my local public library to see if they had this source, a book by T. Harry Williams, biographer of Beauregard. Here’s what he has to say about this issue:

"With War Department approval of his idea [for a new battle flag], Beauregard eagerly proceeded to get his first flags made while the army was in winter quarters. They were manufactured in the best tradition of Southern romance. At the time the three Cary girls [basically Confederate groupies] were on one of their periodic visits to camp. It was decided that they would contribute material from their dresses to make flags[...]. Material for additional flags would be procured from other ladies. Because of the origin of the silk in the first emblems, the backgrounds were more of a feminine pink than a martial red" (109-110; italics mine).

In the footnotes, besides letters in the Archives at the Library of Congress, the sources of this claim are cited as including “a multitude of letters on the origin of the battle flag in the Beauregard Papers (Confederate Hall, New Orleans) and in the Confederate Flag Correspondence (Confederate Museum, Richmond).” Seems legit.

That the earliest iteration of the rebel banner looks to modern eyes like it was made by a middle-school girl out of Starbursts may come as a shock to Yankees and Southerners alike. But as far as I can tell this odd little bit of flag history is true.

Sources:

Ward, Drew. "The official design of the Confederate Battle Flag per General PGT Beauregard's original design." Wikimedia Commons, 2015. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P._G._T._Beauregard#/media/File:Confederate_Battle_Flag_%28official_design%29.png. Accessed 19 June 2017.

Williams, T. Harry. P.G.T. Beauregard: Napoleon in Gray. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1954.

"With War Department approval of his idea [for a new battle flag], Beauregard eagerly proceeded to get his first flags made while the army was in winter quarters. They were manufactured in the best tradition of Southern romance. At the time the three Cary girls [basically Confederate groupies] were on one of their periodic visits to camp. It was decided that they would contribute material from their dresses to make flags[...]. Material for additional flags would be procured from other ladies. Because of the origin of the silk in the first emblems, the backgrounds were more of a feminine pink than a martial red" (109-110; italics mine).

In the footnotes, besides letters in the Archives at the Library of Congress, the sources of this claim are cited as including “a multitude of letters on the origin of the battle flag in the Beauregard Papers (Confederate Hall, New Orleans) and in the Confederate Flag Correspondence (Confederate Museum, Richmond).” Seems legit.

That the earliest iteration of the rebel banner looks to modern eyes like it was made by a middle-school girl out of Starbursts may come as a shock to Yankees and Southerners alike. But as far as I can tell this odd little bit of flag history is true.

Sources:

Ward, Drew. "The official design of the Confederate Battle Flag per General PGT Beauregard's original design." Wikimedia Commons, 2015. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P._G._T._Beauregard#/media/File:Confederate_Battle_Flag_%28official_design%29.png. Accessed 19 June 2017.

Williams, T. Harry. P.G.T. Beauregard: Napoleon in Gray. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1954.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed